Every-body has stories.

Stories tell you who you are, who they are.

This is the stories of roots, the identity.

Express yourself on a canvas of omusubi.

Share the taste of the stories with others?

Stories tell you who you are, who they are.

This is the stories of roots, the identity.

Express yourself on a canvas of omusubi.

Share the taste of the stories with others?

Stories of Roots (SoR) is a socially-engaged-artwork aiming to bring a shift against racism and any other social oppression. SoR invites you to explore people’s stories by using omusubi. It is a place where people meet different people.

Through making or eating Omusubi, people will embrace relational, cultural and symbolic values of identities of yourself as well as others. SoR believes knowing the stories enables us to re-humanize.

Through making or eating Omusubi, people will embrace relational, cultural and symbolic values of identities of yourself as well as others. SoR believes knowing the stories enables us to re-humanize.

Omusubi is a bridge between people from different backgrounds.

To know more details,

Theory

This is a case study of socially engaged art (SEA) that uses Omusubi, a rice ball filled with different ingredients, with an Islamic community in Arnhem. The project is called “Stories of Roots” (SoR), aiming to bring re-humanization in the societies. “Embodiment” and an “empathic pedagogy” are the fundamental disciplines in this project. In this text, I will argue about the meanings of those terms in my practice in relation to socially engaged art.

As an acknowledgement at first, embodiment in my research is based on the notion of monism which is not separation between body and mind, in other words, it is not one sole discipline but it is referred to Dolphijn and Tuin (2011) and Blackman (2008) that regard it as comprehensive interdisciplinary in relation to psychological, sociological, physical, and symbolical perspectives. Embodiment happens every moment in interactions with self and others. My research put a position of embodiment as a “socially mediated phenomena” (Turner, 1984).

To be more specific, embodiment means bodily activities using sensation, which entails learning. The bodily activities and sensations are significant in terms of pedagogy since it allows the body as the centre of knowledge, and makes leaning as an ongoing phenomena of embodied knowledge (Springgay, 2011) and a horizontal relationship between people (Freire, 1970).

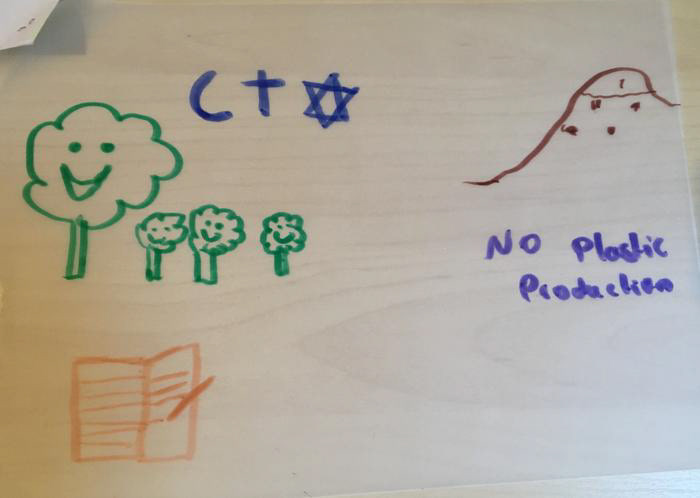

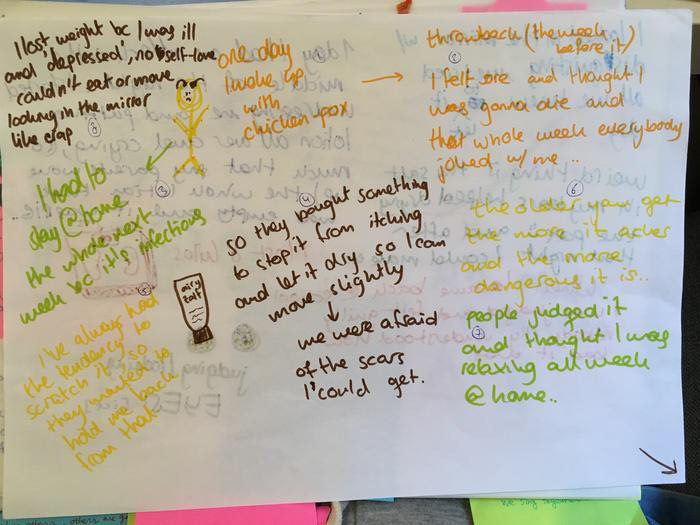

The empathic pedagogy is an activity that leads new perspectives with empathy, and learning that are fostered by dialogue (Bohm, 1996), which is not always verbal but also non-verbal such as drawings, and smelling and making food. Freire (1970) claimed that Love, faith, humility, hope, critical thinking, and solidarity are vital for dialogue. I believe that these are also fundamental for “empathy”. In other words, one of the essences of the dialogue is an empathic relation, which I call the empathic pedagogy as it contributes to shifting people’s perspectives and emancipation (Freire, 1970). I would note that empathy involves an authentic understanding of self and others, which is important to humanize. Furthermore, embodiment is also honest and authentic (Blackman, 2008) since it emerges with feelings that are the first place where people react (Shaviro, 2009). Therefore the authentic understanding is reinforced by sensory activities. Moreover, referring to Blackman(2008) and Burke and Stets (2009), sensory activities are useful for exploring identity, sensation and perception. The activities/workshops of Stories of Roots foster those processes by using their own bodies and interacting to others.

Thus, it could be noted that empathy, dialogue, and embodiment are crucially correlated. They are enhanced by the interplay with different resources such as bodies of yourself and others, and food, since Burke and Stets (2009) has stated that 'anything that supports individuals and their interaction is a resource. Food is a resource, not an entity, and is a process that includes ingesting, digesting, circulating, and chemically using and transforming food’ (p.101-101).

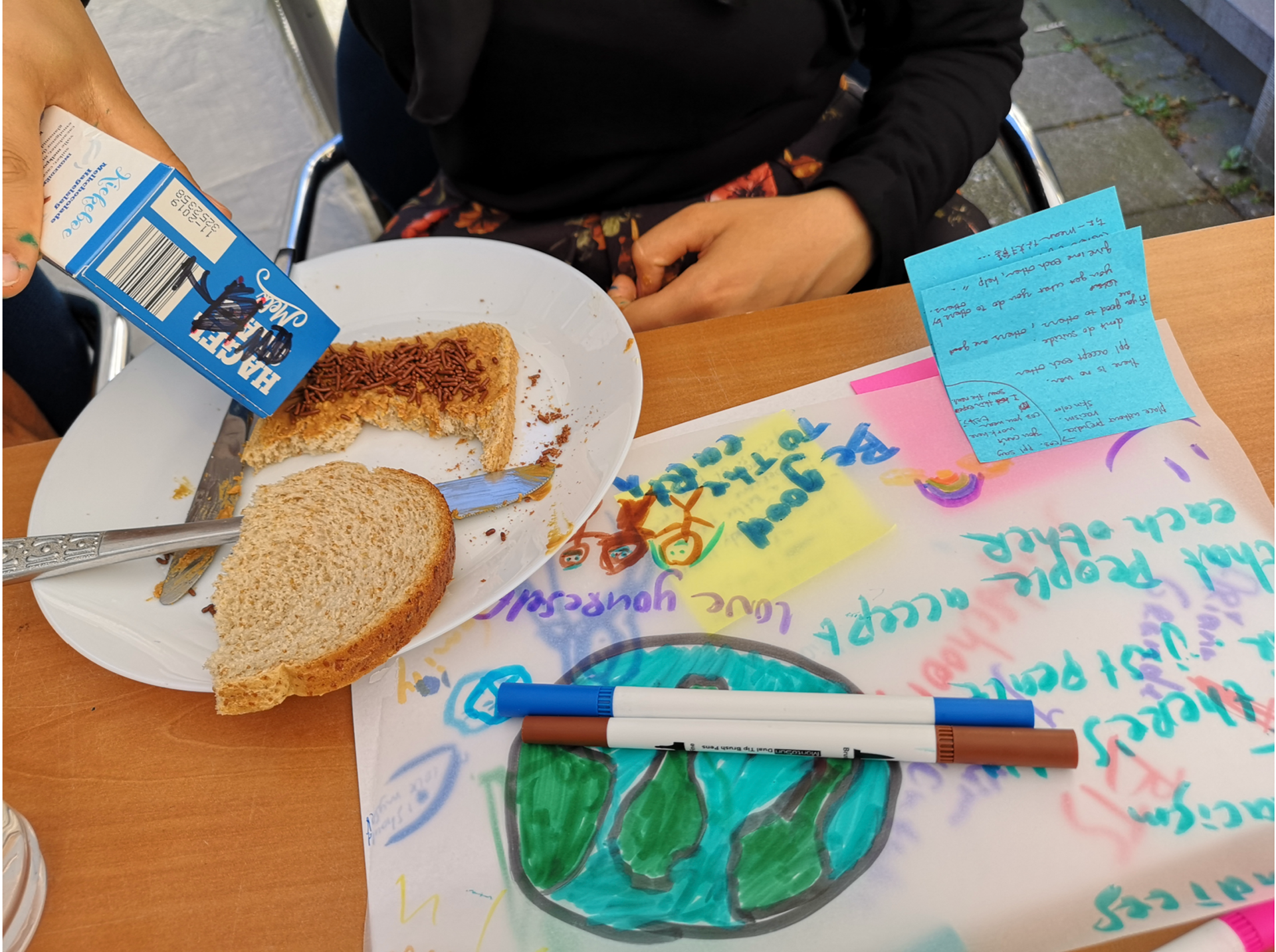

In this case study, those embodied activities that enables the empathic pedagogy were utilised. I worked with an Islamic community in Arnhem. It is a centre as well as an accommodation for muslim girls age between 13 and 19 years old, and mostly from Turkey. The teachers are also muslim and living with the students at the centre and teach Islam and help their school study.

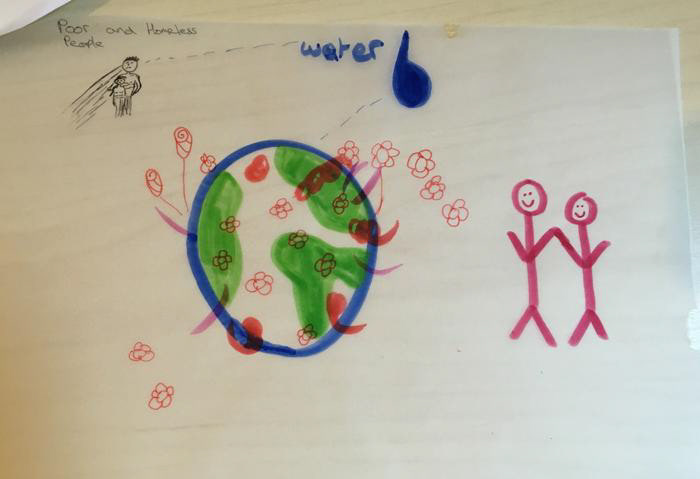

As an socially engaged art (SEA) project, the process itself is already an art and significant, however, more importantly it should be “engaging” rather than simply defining all process-based art are SEA (Helgueara, 2011). Considering it, the basic purpose of this project is to engage people from different groups by making, eating, and sharing Omusubi. It aims to create a place where people explore their stories as well as others, which is hoped to bring a “shift” in the society and re- humanization. Indeed, the community was involved in the process of making the Omusubi. After several times of my visit to the centre and workshops, five students came to me voluntarily to continue participating in the project. They transformed their stories into Omusubi at the workshop, which I will explain more later in the text.

The image-a below indicates how the whole system of SoR works in terms of an economic level of embodiment. SoR was designed with two principal activities: 1) workshop (the right one towards the image-a), and 2) selling Omusubi as a product (the left one towards the image-a). In the workshop, embodiment and the empathic pedagogy directly emerge throughout the process by using resources such as bodies and food. Regarding the latter, although it might sound and look like just a normal product, it has some layers to lead the shift towards re-humanization as well as engagement with different groups of people. Omusubi that is sold is made by people’s stories which were produced in the workshop. In this case, the five girls from the community are the ones who initially made the Omusubi. Therefore, when the consumers buy the Omusubi, they will know the stories of the girls, which would hardly be known without any mediators. So to say, the targets for the workshop and for the products are different. While the workshop are mainly targeting to some ethnic minority groups, the products aim to approach to those who are simply interested in the food.

As the final stage of this model which is “making it into public” (selling the Omusubi as a product), I opened a one day shop of SoR at a Westerpark in Amsterdam in a collaboration to a Japanese community. That was a part of a Japanese art festival and I was presenting with two different artists in the place. Since the shop was held as a part of the art festival and at the park, the audiences were mostly those who are interested in the art activities or those who were just in the park for other reasons. Therefore, that was indeed a good connection between people from the community and the others.

To have both products and workshop is necessary for this model as it is correlational, which allows a sustainable system. To maintain the workshop, the financial support comes from the profit of Omusubi as a products while the workshop contributes to making Omusubi since it is made by people’s stories. Although the actual practice at the park failed earning the profit enough to give the community some money, it is hoped to give some of the profit to the community for a sustainable system in the future.

In order to make the audiences know the stories, I designed a package of Omusubi (see picture 1). To give the Omusubi, it is wrapped by the paper that has a description of ingredients as well as a recipe of the Omusubi, which tell the story of the girls who initially made the Omusubi, on it. The ingredients and the recipe are namely the metaphors of the stories as it does not show actual name of the food or steps of how to make it. Once they open the package, they see the contents, and to see more details of the story, you can follow the link shown on the paper (cf: https://storiesofroots.cargo.site/ ). This process for the audiences (customers) has embodiment and the empathic pedagogy in smelling and eating the Omusubi as it is an sensory activity with their body, and knowing the story leads empathy and a new perspective about the community. For the other contents in the image-a, it will be explained in the assessment.

Embodiment and the empathic pedagogy have emerged in the workshop too. The making process at the workshop is the essential points of this project. This is one of the reasons why I use Omusubi since Omusubi invites people to activate their sensory such as smelling, touching, and tasting, and making their own Omusubi by their hands. Omusubi is meant to be a metaphor of the person’s stories, and a canvas for them to transform their stories since they can freely make it with different ingredients following their intuitions and concepts. The stories which were elaborated by sensory activities during the workshop tell authentically who the person is since the relation between the authenticity and sensation is correlated. In addition, the term “musubi” has a meaning of “tie, unite, join, and connect” in Japanese, which is also the reason why I use Omusubi as a main tool.

With the five girls from the Islamic community, we started to discover their stories deeply followed by steps I made, which you can find in ELO folder or the paper I give at the assessment. It was design by referring to some theories such as Karl Weick’s sense making, and Kunitake Saso’s vision driven. In the theory of Weick (1995), he indicated 3 steps: 1) Scanning Sense, 2) Interpretation, and 3) Enacting. In each step, input and output are repeated. Similarly, Saso (2019) proposed 4 components of vision driven which is different from problem solving thinking. The components are these followings: Drive, Input, Jump, and Output. Some of the elements in those theories were important in my process of making the own methodology, yet, I adapted mostly the steps of Non-violent communication (NVC), which includes these following steps: 1) Observe the fact, 2) Focus on Feelings you had, 3) Dig into what you actually NEED, and 4) Request (Leu, 2015).

The image-b shows how the workshop and the product work pedagogically. Both are consisted of the same elements which are sensation, observation, interpretation, and imagination. In both circles, the empathic pedagogy and embodiment are happening by interacting with resources.

The left part towards the image is about the product while the right is about workshop. Both components are not in order. It can be started from anywhere since learning occurs in all the stages. For the workshop, imagination is about drawing and sharing their ideal world/future. At the sensation stage, the participants interact with ingredients by sensory activities such as smelling and tasting, and draw the significant events or memories they remember. The participants transform their stories into Omusubi afterwards. For the products, sensation means smelling, seeing, or eating Omusubi while imagination is enriched by knowing the stories. The Omusubi is a mediated product to make a connection between the community and them, and to shift their perspectives.

Those images I introduced are the models of embodiment which enables the empathic pedagogy as an economic perspective (image-a) and a perspective of personal interaction (image-b). Although the whole contents were not included in this testimony, the predominant two functions: products and workshop, were implemented in the context of socially engaged art practice with the Islamic community, using Omasubi as a mediator. It is hoped to be developed with more practice after the graduation.

Conclusion

Embodiment and the empathic pedagogy are understood as holistic disciplines and ground on the notion of monism, which sees body as not separation but it is deeply interconnected (Blackman, 2008). Having this idea as an acknowledgement, the graduation project was implemented as a case study of a socially engaged art that entails a correlation between the embodied activities and the empathic pedagogy as a personal level and an economic level. The correlation between them is essential to bring a shift in the society since Freire (1970) and Bohm (1966) has noted that dialogue, which requires an authenticity and an interaction between resources, is crucial to understand others. The authentic dialogue entails empathy, which is a key for change. Authenticity can be reinforced by embodied activity as it allows the body as the centre of knowledge (Springgay, 2011), and a horizontal relations between people (Freire, 1970), moreover, as it is authentic and honest (Blackman, 2008). The models hope to connect people from different groups, in particular, between ethnic minority groups and others in order for re-humanization. Stories of Roots is a continuous project, which is expected to be developed further after the graduation for a sustainable change in the society.

Reference

Blackman, L. (2008). The Body. New York and Oxford: International Publishers Ltd.

Bohm, D. (1996). On Dialogue. London: Routledge.

Burke, P.J. and Stet, J.E. (2009). Identity Theory. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Dolphijn, R. and Tuin, I. D. (2012). New Materialism: Inter views & Cartographies. University of Michigan Library. Open Humanities Press.

Freire, P. (1970) Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York and London: Continuum.

Helguera, P. (2011). Education for Socially Engaged Art. NY: Jorge Pinto Books Inc.

Leu, L. (ed.) (2015) Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life. Encitas: PuddleDancer Press.

Saso, K. (2019). Vision Driven. 直感と理論をつなぐ思考法 . Tokyo: Diamond Inc.

Shaviro, S. (2009). Without criteria: Kant, Whitehead, Deleuze, Aesthetics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Springgay, S. (2011). The Chinatown Foray as Sensational Pedagogy. Oxford: Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Turner, B. (1984), The Body and Society: Explorations in Social Theory. 1st edn. Oxford and New York: Blackwell.

Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in Organizations. Thousand Oaks, London, New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Bohm, D. (1996). On Dialogue. London: Routledge.

Burke, P.J. and Stet, J.E. (2009). Identity Theory. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Dolphijn, R. and Tuin, I. D. (2012). New Materialism: Inter views & Cartographies. University of Michigan Library. Open Humanities Press.

Freire, P. (1970) Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York and London: Continuum.

Helguera, P. (2011). Education for Socially Engaged Art. NY: Jorge Pinto Books Inc.

Leu, L. (ed.) (2015) Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life. Encitas: PuddleDancer Press.

Saso, K. (2019). Vision Driven. 直感と理論をつなぐ思考法 . Tokyo: Diamond Inc.

Shaviro, S. (2009). Without criteria: Kant, Whitehead, Deleuze, Aesthetics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Springgay, S. (2011). The Chinatown Foray as Sensational Pedagogy. Oxford: Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Turner, B. (1984), The Body and Society: Explorations in Social Theory. 1st edn. Oxford and New York: Blackwell.

Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in Organizations. Thousand Oaks, London, New Delhi: Sage Publications.